19 May 2018

A Report on the Review Process of ACL 2018

Reviewing is an essential building block of a high-quality conference. However, the quality of reviews for ACL conferences has been increasingly questioned recently. However, ensuring and improving review quality is perceived as a great challenge. One reason is that the number of submissions is rapidly increasing, while the number of qualified reviewers is growing more slowly. Another reason is that members of our community are increasingly suffering from high workload, and are becoming frustrated with an ever-increasing reviewing load.

In order to address these concerns, the Program Co-Chairs of ACL 2018 carefully considered a systematic approach and implemented some changes to the review process in order to obtain as many high-quality reviews as possible at a lower cost.

A large pool of reviewers

A commensurate number of reviewers is necessary to review our increasing number of submissions. As reported previously (see Statistics on submissions and reviewing), the Program Chairs asked the community to suggest potential reviewers. We formed a large pool of reviewers that includes over 1,400 reviewers for 21 areas.

The role of the area chairs

The Program Chairs instructed area chairs to take responsibility for ensuring high-quality reviews. Each paper was assigned one area chair as a "meta-reviewer". This meta-reviewer kept track of the reviewing process and took actions when necessary, such as chasing up late reviewers, asking reviewers to elaborate on review comments, leading discussions, etc. Every area chair was responsible for around 30 papers throughout the reviewing process. The successful reviewing process of ACL 2018 owes much to the significant amount of effort by the area chairs.

When the author response period started, 97% of all submissions had received at least three reviews, so that authors had sufficient time to respond to all reviewers' concerns. This was possible thanks to the great effort of the area chairs to chase up late reviewers. A majority of reviews described the strengths and weaknesses of the submission in sufficient detail, which helped a lot for discussions among reviewers and for decision-making by area and program chairs. (See more details below.) The area chairs were also encouraged to initiate discussions among reviewers. In total, the area chairs and reviewers posted 3,696 messages for 1,026 papers (covering 66.5% of all submissions), which shows that intensive discussions have actually taken place. The following table shows the percentages of papers that received at least one message for each range of average overall score. It is clear that papers on the borderline were discussed intensively.

| Avg Score | Long Papers | Short Papers |

|---|---|---|

| 6>x≥5 | 40.0% | 0.0% |

| 5>x≥4 | 70.7% | 66.7% |

| 4>x≥3 | 81.3% | 79.8% |

| 3>x≥2 | 59.4% | 57.0% |

| 2>x≥1 | 36.1% | 30.0% |

Structured review form

Another important change in ACL 2018 is the structured review form, which was designed in collaboration with NAACL-HLT 2018. The main feature of this form is to ask reviewers to explicitly itemize strength and weakness arguments. This is intended…

…for authors to provide a focused response: In the author response phase, authors are requested to respond to weakness arguments and questions. This made discussion points clear and facilitated discussions among reviewers and area chairs.

…for reviewers and area chairs to understand strengths and weaknesses clearly: In the discussion phase, the reviewers and area chairs thoroughly discussed the strengths and weaknesses of each work. The structured reviews and author responses helped the reviewers and area chairs identify which weaknesses and strengths they agreed or disagreed upon. This was also useful for area chairs to evaluate the significance of the work for making final recommendations.

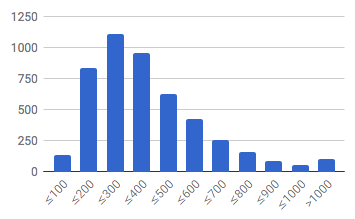

In the end, 4,769 reviews were received, 4,056 of which (85.0%) followed the structured review form. The following figure shows the distribution of word counts of all reviews. The majority of reviews had at least 200 words, which is a good sign. The average length was 380 words. We expected some more informative reviews – we estimated around 500 words would be necessary to provide strength and weakness arguments in sufficient detail – but unfortunately we found many reviews with only a single sentence for strength/weakness arguments. These were sufficient in most cases for authors and area chairs to understand the point, but improvements in this regard are still needed.

Another important change was the scale of the overall scores. NAACL 2018 and ACL 2018 departed from ACL’s traditional 5-point scale (1: clear reject, 5: clear accept) by adopting a 6-point scale (1: clear reject, ..., 4: worth accepting, 5: clear accept, 6: award-level). In the ACL 2018 reviewing instructions, it is explicitly indicated that 6 should be used exceptionally, and this was indeed what happened. (See the table below.) This had the effect of changing the semantics of scores, and, in contrast to the traditional scale, reviewers tended to give a score of 5 to more papers than in previous conferences. The following table shows the score distribution of all 4,769 reviews (not averaged scores for papers). Refer to the NAACL 2018 blog post for the statistics for NAACL 2018. The table shows that only 13.5% (long papers) and 6.8% (short papers) of reviews give “clear accepts”; more importantly, the size of the next set (those with overall score 3 or 4) was very large &emdash; too many to include in the set of accepted papers.

| Overall Score | Long Papers | Short Papers |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 0.4% | 0.1% |

| 5 | 13.1% | 6.7% |

| 4 | 31.9% | 26.8% |

| 3 | 27.0% | 29.0% |

| 2 | 21.2% | 29.0% |

| 1 | 6.4% | 8.3% |

Another new feature of the review form was the option to "Request a meta-review". This was intended to notify area chairs to look into the submission carefully, as the reviewer’s evaluation was problematic for some reason (e.g., the paper had potential big impact but was badly written). In total, 274 reviews contained a request for a meta-review. For these cases, the area chairs read the paper in depth by themselves when necessary.

Review quality survey

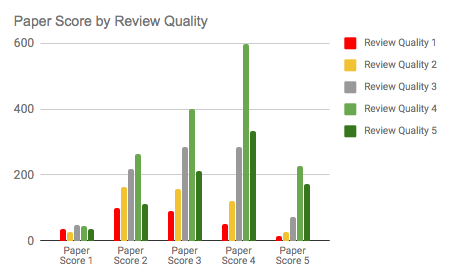

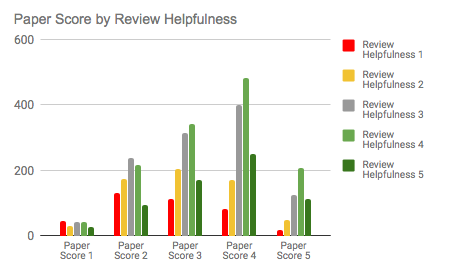

The Program Chairs asked the authors to rate the reviews. This was mainly intended for future analysis of good/bad reviews. The following graphs show the relationship between overall review scores (x-axis) and survey results (review quality and helpfulness). It shows review quality/helpfulness scores tend to be higher for high-scoring papers (probably authors appreciated high scores), while low-scoring papers also still received a relatively high percentage of positive review quality/helpfulness scores.

More detailed in-depth analysis will be conducted in a future research project. Also, reviews and review quality survey results will be partly released for research purposes in an anonymized form.

Review process

In this section, we describe the detailed process of reviewing and decision-making.

-

After the submission deadline, the Senior Area Chairs assigned an Area Chair and reviewers to each paper.

The Program Chairs determined the initial assignments of Area Chairs to each paper using the Toronto Paper Matching System (TPMS). The Senior Area Chairs adjusted the assignments themselves as necessary.

Next, the area chairs assigned at least three reviewers to each paper. This process employed TPMS and reviewer bidding results, but the area chairs determined final assignments manually, considering the specific research background and expertise of the reviewers, and the maximum number of papers that a reviewer could be assigned.

-

After the review deadline, the area chairs asked the reviewers to improve reviews where necessary.

Each area chair looked into reviews of their assigned papers and asked the reviewers to elaborate on or correct reviews when they found them uninformative or unfair. This was also performed on receipt of author responses (during the discussion phase).

-

After the author response period, the area chairs led discussions among reviewers.

The Program Chairs asked the area chairs to initiate discussions among reviewers when necessary. In particular, they asked reviewers to justify weakness arguments when they were not clearly supported. As shown above, a lot of discussions happened during this phase, helping reviewers and area chairs to more deeply understand the strengths and weaknesses of each paper. See the “Statistics” section for the effect of author responses and discussions.

-

After the discussion period, the area chairs produced a ranked list of submissions.

The Program Chairs asked the area chairs to rank all submissions in their area. They explicitly instructed them to not simply use the ranking resulting from the average overall scores. Instead, the Program Chairs asked the area chairs to consider the following:

-

The strengths and weaknesses raised by reviewers and their significance

-

The result of discussions and author responses

-

The paper’s contribution to computational linguistics as a science of language

-

The significance of contributions over previous work

-

The confidence of the reviewers

-

Diversity

Area chairs were asked to classify submissions into six ranks: "award-level (top 3%)", "accept (top 15%)", "borderline accept (top 22%)", "borderline reject (top 30%)", "reject (below top 30%)", and "debatable". They were also asked to write a meta-review comment for all borderline papers and for any papers that engendered some debate. Meta-review comments were intended for helping the Program Chairs arrive at final decisions, and were not disclosed to authors. However, we received several inquiries from authors regarding the decision-making process by area chairs and program chairs. Providing meta-review comments to authors in the future might help to make this part of the review process more transparent. If this process is adopted, then the area chairs should be instructed to provide persuasive meta-reviews that explain their decisions and that can be made accessible to the authors.

-

The Program Chairs aggregated the area recommendations and made final decisions.

The Program Chairs analyzed the recommendations from area chairs to make the final decisions. They were able to accept most "award-level" and "accept" papers, but a significant portion of "borderline accept" papers had to be rejected because the "accept" and "borderline accept" together already significantly exceeded the 25% acceptance rate. The Program Chairs analyzed the reviews and meta-review comments to accept papers from the "borderline accept" and occasionally the "borderline reject" ranks, calibrating the balance among areas. When necessary, they asked the area chairs to provide further comments. A significant number of papers (including "debatable" papers) remained until the very end, and the Program Chairs read these papers themselves to make a final judgment.

The Program Chairs also closely examined the papers satisfying the following conditions, in order to double-check the fairness of decisions:

-

Decisions in contradiction with the area chair recommendations (e.g., papers rejected although the area chairs recommended "borderline accept")

-

Accepted papers with an average overall score of 4 or less

-

Rejected papers with an average overall score of 4 or more

In the future, all papers meeting these criteria should require a meta-review, along with some kind of explanation of how to improve the work as well as an acknowledgement of the work that went into the rebuttal.

-

Statistics

In the end, we accepted 258 of 1018 long papers, and 126 of 526 short papers. This makes the acceptance rate: 25.3% for long papers, 24.0% for short papers, and 24.9% overall.

While we instructed the area chairs not to rely on average overall scores, obviously there should be some correlation between overall scores and acceptance. The following tables show acceptance rates for each range of overall scores. It shows that ACL 2018 was very competitive, as many papers with an average overall score of 4 or higher were rejected. However, it also shows that some papers that received a low score also got accepted, because area chairs looked into the content of papers rather than relying only on the scores.

In addition, some areas had a lot of high-score papers, while some others did not, so such effects were factored by the Program Committee chairs when making the final decisions.

| Avg Score | Long Accept Rate | Short Accept Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 6>x≥5 | 100% | 100% |

| 5>x≥4 | 70.7% | 90.8% |

| 4>x≥3 | 7.6% | 23.6% |

| 3>x≥2 | 0.0% | 0.5% |

| 2>x≥1 | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Min Score | Long Accept Rate | Short Accept Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 100% | 100% |

| 4 | 77.8% | 92.8% |

| 3 | 22.3% | 35.5% |

| 2 | 2.4% | 5.7% |

| 1 | 1.5% | 1.0% |

| Max Score | Long Accept Rate | Short Accept Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 83.3% | 0.0% |

| 5 | 65.2% | 82.9% |

| 4 | 14.3% | 28.0% |

| 3 | 0.0% | 1.2% |

| 2 | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 1 | 0.0% | 0.0% |

The following table shows how the scores or comments of each review changed after the author response and the discussion phase. Around half of the papers on the borderline received some change in scores and/or review comments.

| Avg Score | Score Changed | Score Increased | Score Decreased | Review Comments Changed | Score or Review Comments Changed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6>x≥5 | 15.0% | 0.0% | 15.0% | 25.0% | 25.0% |

| 5>x≥4 | 30.6% | 20.6% | 9.5% | 30.9% | 43.5% |

| 4>x≥3 | 45.8% | 24.1% | 24.1% | 44.3% | 61.6% |

| 3>x≥2 | 20.7% | 7.0% | 15.3% | 25.6% | 36.0% |

| 2>x≥1 | 5.2% | 5.2% | 0.0% | 11.2% | 12.1% |

Author responses were submitted for 1,338 papers. Of these papers, 685 (51.2%) saw some change in scores and/or review comments. Such changes also occurred for 24 of the 206 (11.7%) papers without an author response. This indicates that author responses have an effect of changing scores/reviews (although not necessarily positively).

Main Observations and Recommendations

The ACL community is growing, and we need more mature and more stable conference structures.

We have found the following innovations to be particularly beneficial:

-

Introducing a hierarchical PC structure, specifically the role of Senior Area Chair

-

Restricting the workload of each Area Chair to a maximum of 30 papers

-

The use of TPMS for rough reviewing assignments

-

The use of automatic formatting checks before paper submissions

-

Having Area Chairs propose acceptance decisions based on a qualitative analysis of the reviews (as opposed to scores) and write meta-reviews for the majority of borderline papers

-

Structured review forms with strength/weakness arguments

The Program Chairs also encountered a number of issues that should be addressed as a community-wide effort for further improving the quality of the review process and conferences. The following areas require the attention of the community in the future:

-

Implementing more automatic support for various steps of the reviewing process as part of a reviewing infrastructure;

-

Having area chairs write persuasive meta-reviews to be provided to the authors to ensure the transparency of the final decisions and the future improvement of a paper;

-

Better support for COI handling, including professional conflicts – e.g., introducing the role of a compliance officer;

-

Strong expectations regarding the reproducibility of each paper’s results by making the data and the software freely available and easily executable;

-

Measures to provide training and guidance for graduate students involved in reviewing papers as main reviewers – e.g., mentoring by their PhD advisors and/or area chairs;

-

Better guidelines regarding the overlap with parallel submissions, between short and long version of the same paper, non-archival conferences (e.g., LREC), etc.;

-

Possibly accepting more high-quality papers to the conference.

Overall, ACL conferences are super-competitive, and many very good papers cannot be accepted since the conference space is limited. On the one hand, keeping the acceptance rate under 25% is important for structural reasons like top conference rankings. On the other hand, more inclusive strategies are needed to accommodate more papers qualifying for acceptance which would otherwise have to be rejected.